Two vastly important geopolitical developments have dominated the international spectrum in recent months – the escalating crisis in Ukraine, and the ever-increasing diplomatic and economic synergy between Xi Jinping’s China and Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Any approach to the former must heavily consider the subsequent ramifications upon the latter.

The heretofore informal Sino-Russian alliance – recently coined by the Wall Street Journal as the “New Axis of Autocracy” – experienced substantial scaling via the highly publicized joint statement between Xi and Putin on the eve of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. The 5,000 word pronouncement covers significant ground, referencing deepening economic ties, jointly developed security orientations, and a commitment to national sovereignty at home and abroad.

While the two countries do not yet enjoy a formal alliance, that is an eventuality that should concern anyone who values freedom and democracy, anywhere in the world. Now situated opposite the United States as a clear rival hegemon – a la the Soviet Union in decades past – the Chinese Communist Party has steadily increased its power and reach by folding new allies into China’s totalitarian embrace.

Adding Russia to its repertoire would be the feather in China’s cap, resulting in a substantially more formidable Iron Curtain than the Soviet Union ever achieved; this time extending from Moscow to Beijing.

The current orientation of the United States and its NATO allies towards the Ukraine situation could significantly increase the likelihood of such an alliance, and hasten its development.

Perhaps the most relevant piece of the aforementioned mutual statement is its pledge to combat further NATO expansion: “The sides oppose further enlargement of NATO and call on the North Atlantic Alliance to abandon its ideologized cold war approaches, to respect the sovereignty, security, and interests of other countries, the diversity of their civilizational, cultural, and historical backgrounds, and to exercise a fair and objective attitude towards the peaceful development of other states.”

While not explicitly stated, this is a clear reference to Ukraine. Putin’s primary demand from the West, in exchange for the drawing down of Russia’s 130,000-plus troops from the Ukrainian border, is a public decision from NATO to permanently deny Ukraine’s admittance and cease its steady eastward encroachment.

On one hand, acceding to the demands of a Russian despot may be difficult to swallow and politically costly, which is why a dominant consensus of western policymakers have drawn a red line around the issue. This stance is especially reasonable if one considers that appeasement’s historical track record has been inauspicious, most notoriously exemplified by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s disastrous policy of catering to Adolf Hitler during the rise of the Third Reich.

However, we must also examine the potential ramifications of not appeasing Putin: namely, pushing him further into the arms of Xi Jinping and the CCP. Though far from an ideal scenario, NATO’s assurances of prohibiting Ukraine’s entry and ceasing its eastward expansion could prevent significantly stronger ties between Russia and China.

While this may seem like we are caving to everything Putin desires, it is important to note a few things.

For one, NATO’s 30 constituent states are nowhere close to allowing Ukraine within the alliance regardless of how this situation plays out. Ukraine does not meet the basic requirements for democratic institutions, individual freedoms, and the rule of law to be considered.

Additionally, Putin is likely genuine in his security concerns; to put things in perspective, President Kennedy immediately girded the United States for World War III upon Nikita Khrushchev’s decision to place ballistic missiles within Cuba in 1962.

The intelligence community increasingly believes that Putin is not bluffing. His military clearly has the offensive capability for a full-scale invasion. Moreover, Putin’s legacy, pride, and reputation amongst rival elites all rest on his emerging from this crisis as a perceived victor.

Furthermore, Putin may even gain domestic support upon invasion; a recent Levada poll reflects that over half of the Russian population blames America and NATO for the growing conflict.

A Russian invasion of Ukraine would subsequently trigger a chain of events that could lead Russia straight to China.

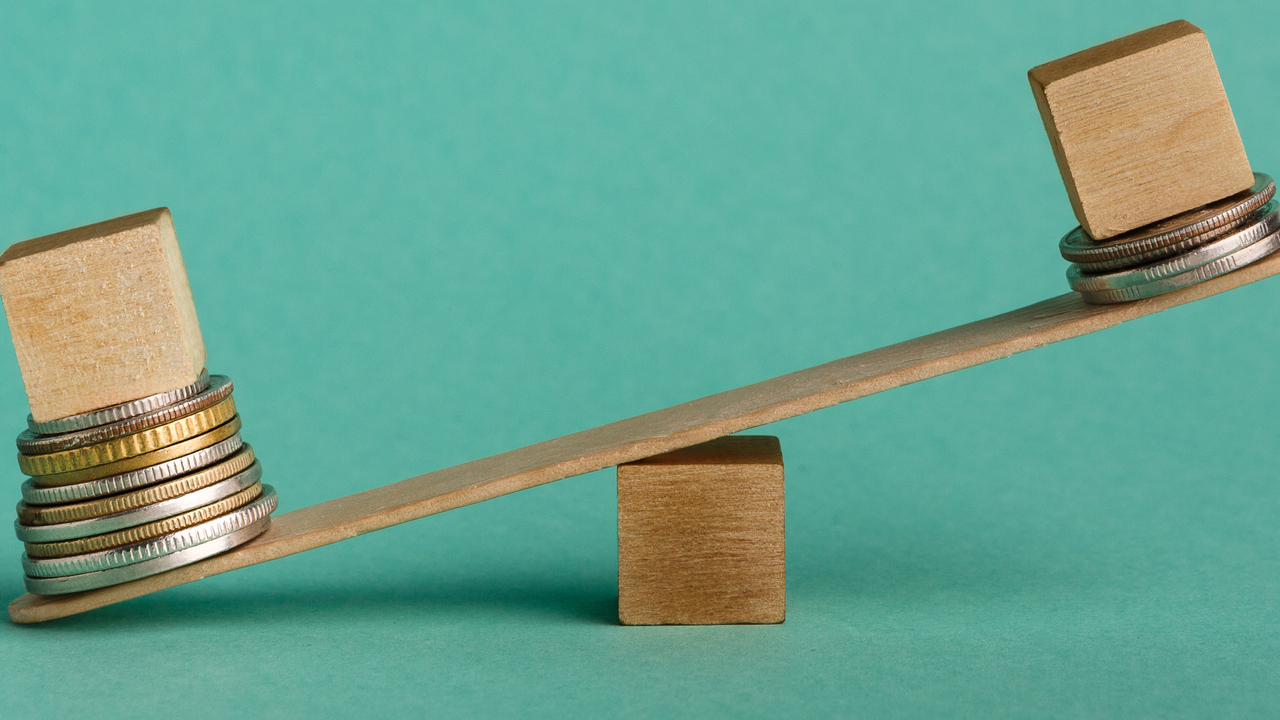

Russia would immediately be met with a comprehensive array of economic sanctions from the United States. Though sanctions historically have had a dubious track record, this package will likely be substantially more effective. Among other aspects, sanctions would cut off western financial investment, prohibit the importation of critical technology, de-value the ruble, choke off Russian export markets, and potentially remove Russia from SWIFT – the western-dominated financial communications consortium that enables banking institutions to process international transactions.

Russia’s economy would be put under tremendous pressure. As Europe is currently Russia’s primary economic partner, any sanctions or other actions that would severely limit that partnership – especially President Biden’s threatened cancellation of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline – would necessitate the transfer of that economic activity to a new source.

China would be only too happy to step in, continuing its trend of offering financial lifelines and general support to any countries disaffected by American intervention, thereby extending the reach of its authoritarian shadow. Not coincidentally, Iran’s recent announcement of a wide-ranging political and economic Chinese alliance is a prime example of a heavily sanctioned state seeking sponsorship from the East.

In fact, it was U.S. sanctions against Russia in response to Putin’s first Ukrainian foray in 2014 that began the greater Sino-Russian economic synthesis, with the two countries signing energy, trade, and finance agreements that have remained largely intact to this day.

We are in the midst of a new Cold War. Though the ideological battle between freedom and totalitarianism remains the same, our new adversary is much more capable than the Soviet Union ever was.

And if the West does not tread very carefully, Russia’s potential addition to China’s autocratic axis could very well tip the balance of power away from the United States for the first time since World War II. This time, communism could win.

First published at: Human Events.

Photo by FMNG.

Jack McPherrin is the managing editor of 1818 Magazine. Jack works as the research editor for the Editorial Department of The Heartland Institute, where he also contributes to the mission of the Socialism Research Center as a research fellow. He is in the final stages of completing his Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Loyola University-Chicago, where his myriad research interests primarily encompass domestic and international economic policy, global institutions, authoritarian regimes, and foreign affairs - with a particular emphasis upon Russia and China. Prior to his graduate pursuits, Jack spent six years in the private sector after graduating from Boston College with a dual Bachelor's Degree in Economics and History. He currently resides in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago, a few short miles from where he was raised.